Anatomy and Physiology: Going Their Separate Ways

Going Their Separate Ways

The most dramatic point in the abdominal aorta is the abrupt division between the two external iliac arteries (and don't forget the parallel joining of the external iliac veins into the inferior vena cava). Abrupt, yes, but illogical, no, as each vessel ultimately goes to a separate leg (refer to Figure 12.1). Since it seems to make sense that they would divide in the pelvis, most people are surprised when they see how high up the split takes place: at about the level of the umbilicus (remember your belly button?). The reason for so high a split makes sense when you realize there is some work left to do, and the split makes it easier.

Remember the body cavities? Well, it's time to look at the “imaginary” pelvic cavity. As the aorta splits, it gives the external iliacs a chance to get out of the way of cramped pelvic organs. With so little space in the pelvis, well, there ain't nowhere for the organs to be but in the middle! This makes it easy to get blood to them; off the external iliac arteries are, you guessed it, internal iliac arteries (with the return trip taking internal iliac veins). Finally, the bulk of the blood goes down and up the legs via the femoral arteries and veins.

Hepatic Portal System

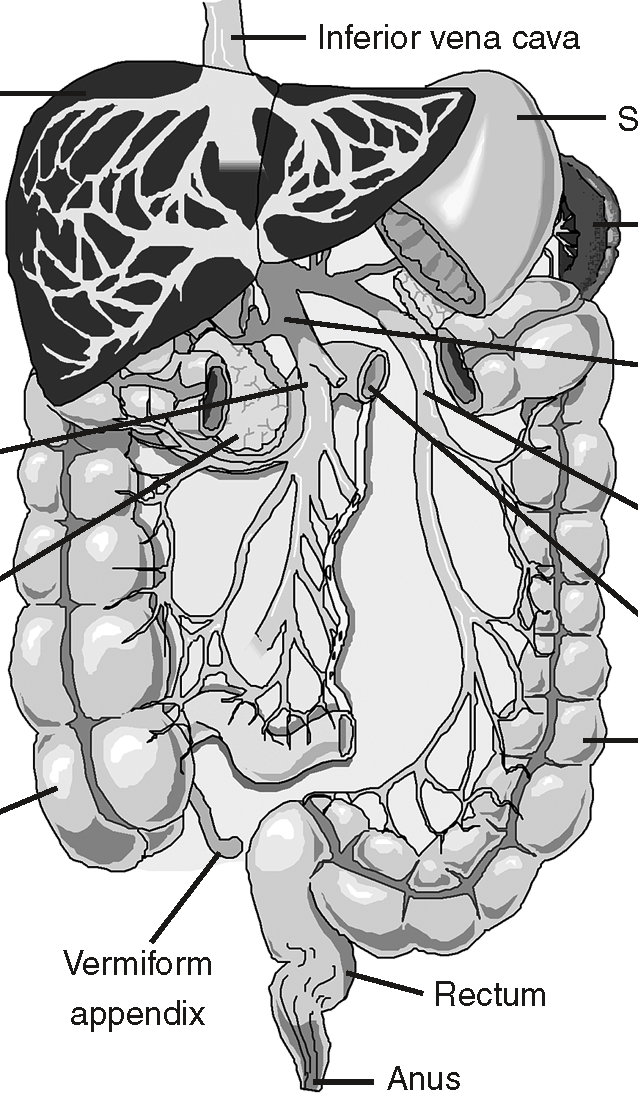

Figure 12.4The hepatic portal vein allows Liver the liver to filter the blood Stomach prior to returning to the heart. (LifeART©1989-2001, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins)

When students lay down the basic blood pathway in their end of the year project (a schematic diagram of all 11 body systems), they start with the arteries, and see the blood leading to the abdominal organs directly from the abdominal aorta. They then make a completely logical assumption and have all the blood return directly to the inferior vena cava, which runs parallel to the aorta. The only problem is that this is wrong!

Medical Records

Just as blood from the heart is not as rich in food as you might expect, that same blood has a lot more waste than you might expect! After all, blood going to nourish the tissues also goes to the kidneys to be filtered of wastes! The “clean” blood from the kidneys ultimately joins up with waste-filled blood before it gets pumped out of the heart again. Thisis all because in the systemic circuit, venous blood always mixes with blood from multiple places before it reaches the heart, but arterial blood is all the same as it branches out from one source!

Blood in vessels from the abdominal organs bypasses the inferior vena cava; the blood travels from capillary beds in those organs directly to capillary beds in the liver. Any vein that travels between two capillary beds is called a portal vein, and since this one goes to the liver—and hepatic refers to the liver—the name of this vessel is the hepatic portal vein (see Figure 12.4). This blood then travels through the liver and ultimately returns to the inferior vena cava via the hepatic vein. Since the blood in the hepatic portal vein is deoxygenated, it means that there needs to be a separate hepatic artery to bring the liver the needed oxygen.

Think of where the blood is coming from: spleen, pancreas, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. The blood from the small intestine, in particular, has a very special quality to it; this blood, carried in the superior and inferior mesenteric veins, has a higher level of food in it than anywhere else in the body! That blood will ultimately mix with blood in other veins, blood that is very low in food, before it is ultimately pumped out of the heart. Blood from the left ventricle may be very rich in oxygen, but it is not that high in food.

When the blood travels to the liver directly from the abdominal organs, the liver immediately goes to work (see The Digestive System for a summary of the liver's functions). The gastrointestinal tract absorbs a lot of toxins, which the liver does its best to break down before sending it to the rest of the body. Excess food absorbed is turned into fat for storage by the liver. Insulin (see Hormones) and glucagon released by the pancreas travel to the liver first, where the liver either starts making glycogen (with insulin) or breaking down stored glycogen (with glucagon).

The Baby's Lifeline

Babies have a very different life than ours. Think about it. They really don't eat, or drink, or even breathe. A growing baby needs an extraordinary amount of energy, not to mention raw materials for growth. All that material must come from its mother, in the ultimate pampering. You know … womb service. Blood must reach the placenta so that material exchange can occur, removing wastes and CO2, taking in food and O2. You might assume that the fetal blood that is the most deoxygenated would go to the placenta, but the body, once again, has some surprises in store.

Although much of the circulation looks the same, it must differ in terms of both the respiratory and digestive systems (see Figure 12.5). Rather than sending blood from the inferior vena cava to the placenta, the blood is arterial! There are two umbilical arteries that branch off of the two internal iliac arteries, and extend onward to the placenta. The developing urinary bladder nests between these umbilical arteries.

Figure 12.5Fetal circulation. Note the two umbilical arteries, the umbilical vein, the foramen ovale, and the ductus arteriosus. (LifeART©1989-2001, RV Lippincott Williams & Wilkins)

The trip back along the single umbilical vein—which, like the pulmonary vein in an adult, carries oxygenated blood—once again does not go directly to the heart. Like the adult, the blood with the most nutrients goes straight to the liver (in the fetus it drains into the ductus venosus, which connects to veins inside the liver), and for all the same reasons. These three vessels, however, are not the only differences. There are two openings in the heart, which disappear after the baby is born.

One opening, called the foramen ovale, connects the right and left atria. This allows blood from the placenta, by going from the right atrium to the left, to bypass the pulmonary circuit and go straight to the systemic circuit. This makes sense, considering that the lungs are not involved in oxygenation yet. The other opening is a connection between the pulmonary trunk and the aorta called the ductus arteriosus; its function is the same as the foramen ovale. These connections close after the baby is born, for the mixture of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood would ultimately be a handicap (and a somewhat reptilian one at that!).

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Anatomy and Physiology © 2004 by Michael J. Vieira Lazaroff. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

To order this book direct from the publisher, visit the Penguin USA website or call 1-800-253-6476. You can also purchase this book at Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble.