Weather: The Greatest One of All

The Greatest One of All

While many might debate whether the 1993 storm was truly the biggest winter storm of the twentieth century, there can be no debate that one of the greatest storms in recorded weather history belongs to another century—the Blizzard of 1888. What a storm! We can only imagine the impact of four feet of snow when the main means of snow removal consisted of horse and buggy.

Actually, there were two Blizzards of 1888. The first struck across the Plains from Montana to Texas and eastward to the Great Lakes. That storm hit on January 12 through 14. The temperature plunged as low as 53 below 0, and more than 200 people died. The second blizzard occurred during mid-March, focusing its energy on the northeast states from Washington, D.C., to New England.

This became the "granddaddy" of all "nor'easters," the East Coast storms that track slowly offshore. As discussed in "On Another Front," they actually arrive from the south, but because the wind comes out of the northeast direction, the storm becomes a nor'easter.

Weather-Speak

A primary center is the initial storm center. A secondary center forms from the primary center. Cyclogenesis is the development or intensification of a cyclone. Bombogenesis has been used to describe extreme cyclogenesis of an explosive nature.

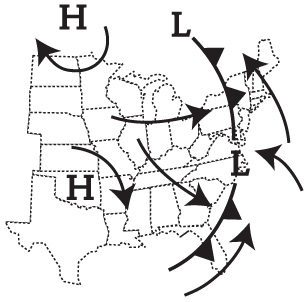

The next three figures show a sequence of weather systems that caused the great Eastern blizzard to occur. It is a classic weather pattern that leads to the development of every nor'easter, but in the case of the March 1888 storm, the weather went to extremes.

March 11, 1888, of the Blizzard of 1888.

The storm had its original energy gather across the Midwest. An initial storm center, called a primary center, pushed into the Great Lakes on March 10. Another system was spinning in the Southern states. It fired into a massive secondary center as the energy from the primary system was transferred to it—a common chain of meteorological events. One center of low pressure will move across the United States and eventually weaken, but enough spin remains to sweep eastward and tap into the temperature contrast found along the East Coast during the winter. Cold air masses sweep around the initial system and clash with the warm air along the coast and adjacent to the warm Gulf Stream waters. The temperature contrast represents that potential energy. The spin that translates from the primary center provides the vertical motion to unleash that energy. An East Coast storm is born. The process is called cyclogenesis, but because these storms can really explode, the process for extreme storms has been dubbed bombogenesis.

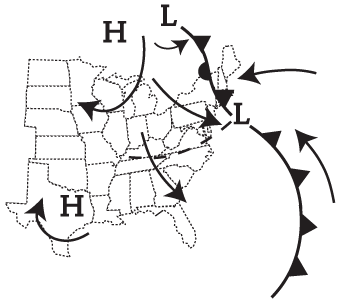

March 12, 1888, of the Blizzard of 1888.

On March 11, the weather was relatively balmy in the Northeast, and a light rain was falling. All accounts of that winter show generally mild conditions—crocuses blossomed early. Everyone was looking forward to spring. As the secondary center pushed off the mid-Atlantic coast, its northeast wind tapped into a cold pool of air that was positioned over eastern Canada. That cold high-pressure system also helped to block the rapid motion of the storm. The storm became stationary near Block Island, where it spun like a top. Much of the rain turned to snow and snowed through March 14.

In these situations, the winds in the upper levels of the atmosphere fail to push the storms along. Those high-level winds simply wrap themselves around the storm. The system becomes caught in an atmospheric whirlpool. The nor'easter can go out of control.

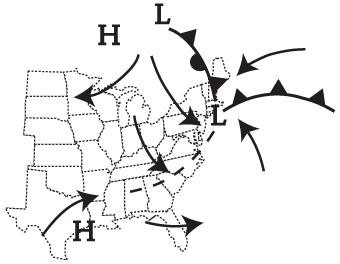

March 13, 1888, of the Blizzard of 1888.

Snowfall depths ranged up to 50 inches over a wide area from the nation's capital to New England. Communication systems were shutdown and transportation was paralyzed. For a week, the northeastern states were cut off from the rest of the world. Snowdrifts of 20 to 40 feet were common. Because the temperature plunged to near zero as winds shifted into the Northeast, slush turned to solid ice. Washington, New York City, Hartford, Albany, and Boston were completely paralyzed. Winds reached hurricane intensity, and an estimated 400 lives were lost. Two hundred people were killed in New York City alone. Some survivors of the storm, called "Blizzard Men of 1888," held annual meetings in New York City until 1941.

Excerpted from The Complete Idiot's Guide to Weather © 2002 by Mel Goldstein, Ph.D.. All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Used by arrangement with Alpha Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.