Mamet's Boy Wonder

An Interview with playwright and filmmaker David Mamet

by Peter Keough |

Related Links |

The only constants, it would seem, in the creative world of David Mamet are that people lie, cheat, steal, betray one another, and talk dirty. Few films have equaled the expletive count of the screen adaptation of his play Glengarry Glen Ross, and the breathtaking bravura of the treachery, cons, and doublecrosses that have unfolded in his films from House of Games to 1998's The Spanish Prisoner have made Mamet an inspiration for a whole generation of nihilist filmmakers.

Indeed, the title of the prescient 1997 film Wag the Dog, which he co-wrote, has become a synonym for the cynical machinations of one of the worst political scandals of all time.

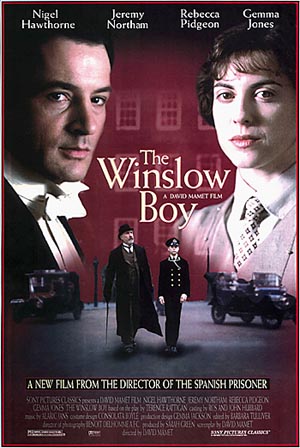

So how account for his latest film, The Winslow Boy? A meticulously crafted, exquisitely performed adaptation of a 50-year-old theatrical warhorse by Terrence Rattigan (it had been adapted for the screen once before by Anthony Asquith in 1950), the film not only contains no offensive language but virtually no offensive behavior.

Based on an actual incident, it's the tale of an ordinary middle-class family in pre-World War I England that sacrifices all to reclaim its honor. Nigel Hawthorne plays Arthur Winslow, a retired banker whose 13-year-old son is expelled from the Royal Naval Academy after being accused of stealing a five schilling postal order.

Aided by his suffragette daughter, played by Mamet's wife Rebecca Pidgeon, and a high-profile barrister played by Jeremy Northam, Winslow engages in a quixotic crusade to prove his boy innocent.

"It's about heroism," says Mamet. "I think we see a similar situation around us all the time. It's the same thing with Susan McDougal. She stood up to a vast, out of control jurisprudential monster. She thought it was right, period. She submitted herself to the worst that they could do because her ideal was higher than theirs. I think it's a great story of heroism; it's one you see not frequently, but regularly."

That McDougal spent time in solitary confinement, while less heroic people like Monica Lewinsky are cashing in with best-selling books, underscores The Winslow Boy's theme.

"One of the things Rattigan's saying in the play is that the reward is not that everything's restored," says Mamet. "You've gone through trauma and the reward is that you got to tell the truth. To the individual it was more important to tell the truth than it was to balance what telling the truth would get them versus what lying would get them."

Did he think audiences who have come to expect in his work an emphasis on lies and deceit versus truth and honor —not to mention somewhat less refined language— might be confused?

"I don't have Tourette's syndrome," he replies. "I'm just a writer. Again, when I was young I spent a lot of time in a certain milieu of society — that's how I made my living, that's how I paid my rent, and I wrote plays about it. I've written a lot of other stuff, too.

"But I think most people go to the movies because there's a movie there. I don't think they care who made it. And I'm not trying to make a statement. I was just drawn to the material. I've been a great fan of Kipling all my life, of Victorian and Edwardian codes of gentility and honor.

"Everybody would like to be a hero, but very few of us, when placed in this position, are going to want to pay the price without second thoughts. That's why the story of the little person who can stand up to authority has the capacity to move us. If these little people just like you or I could act like this in such a situation, then maybe if the time came, I, just like they, could speak truth to power."